British antitrust regulators on Wednesday blocked Microsoft’s $69 billion bid to buy the gaming giant Activision Blizzard, threatening to kill the deal entirely. The ruling raises a broader question: How often do deals fall apart after they’re signed?

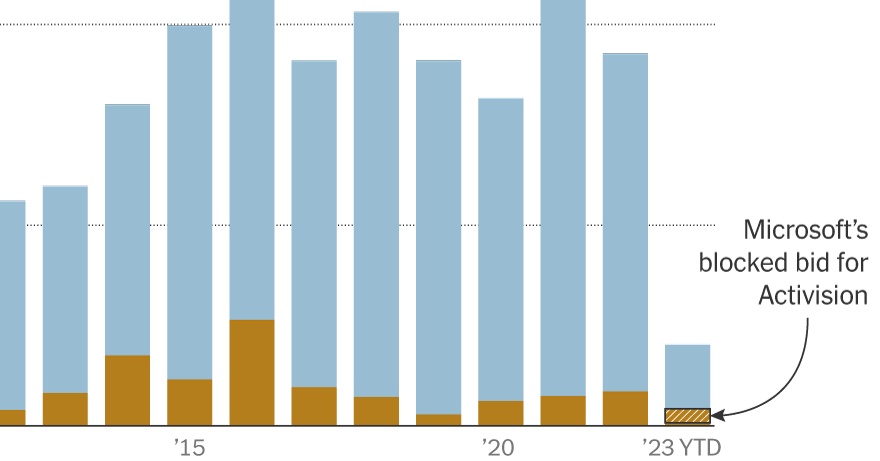

So far this year, just 33 out of 3,347 bids to buy an American company have been withdrawn. Some of the deals may have been signed in previous years, as was the case for the Activision takeover, which was announced last year. In 2022, nearly 12,000 such deals were announced and 142 of them, totaling $170 billion, were withdrawn.

A transaction can fall apart for any number of reasons, but when regulators step in to stop a merger, it’s generally because they have concerns the deal would have a detrimental effect on consumers, or the country at large. Regulators have increasingly been making their case: The number of pulled transactions last year was its highest in 20 years though that may be in part because 2021 had a record number of deals.

One consequence of greater regulatory scrutiny, dealmakers say, is a chill on deal-making: The value of deals announced in 2022 dropped nearly 60 percent from the year prior, though activity in 2021 was notably at a high level.

Dealmakers say it has become increasingly difficult to anticipate when the authorities might move to block a deal or to approve it. This uncertainty is particularly high for companies looking to buy emerging technologies, like those in cloud gaming, as was the case with Microsoft and Activision.

In the United States, there have been a number of headline-grabbing deals that regulators under President Biden have successfully blocked. They include Penguin Random House’s plans to buy Simon & Schuster, and the merger of the insurance giants Aon and Willis Towers Watson, both last year.

Global regulators have been stepping in, too, even for deals involving companies headquartered outside their borders, as Britain did with Microsoft and Activision. The European Union’s competition authority last year moved to block the biotechnology company Illumina’s acquisition of Grail, despite the fact Illumina says Grail has no business in Europe.

Deals can fall apart over national security concerns, too. Broadcom’s acquisition of its rival chip maker, Qualcomm, fell apart after a U.S. government panel argued the deal would give an edge to Chinese companies like Huawei.

Some companies appear willing to place their bets on deals making it through tough inspection. The Justice Department has sued to prevent JetBlue’s acquisition of Spirit Airlines, in a move that had been widely expected given how consolidated the airline industry is already. The two airlines plan to defend their merger, as they push for an outcome similar to UnitedHealth Groups’ purchase of Change Healthcare, after both companies convinced a U.S. District Court judge to overrule a Justice Department suit seeking to block the deal.

Companies seeking mergers know there is a risk the deal will never come to fruition, which is why many contracts include some sort of protection, like a fee that one party pays to the other if regulators break it up. Companies have also been building in longer timelines to close their deals in an effort to fight possible regulatory pushback.

But Britain’s move to stop Microsoft’s bid to buy Activision comes as big technology companies are facing heat and the economic backdrop has made financing deals more difficult. That could point to an even tougher year ahead for what was already a slowing market for deals.