From The Wall Street Journal:

Megan Buskey was raised in a middle-class suburb of Cleveland, a place she describes as “emphatically incurious.” We’re lucky that she is the emphatic opposite, not merely curious—about her own world and the world that her Ukrainian grandmother and mother fled from for America—but driven by a kind of spiritual passion to uncover the secrets that her family had left unaddressed for years.

These secrets were dark, many rooted in World War II, when Ukrainian nationalists had the “uncomfortable history” (in Ms. Buskey’s words) of being allied with Nazi Germany. Her people, she says, “had their reasons for staying quiet about their pasts.” This reticence was compounded in the postwar Soviet Union, in which Ukrainians were “schooled in the consequences of revealing too much to the wrong person.”

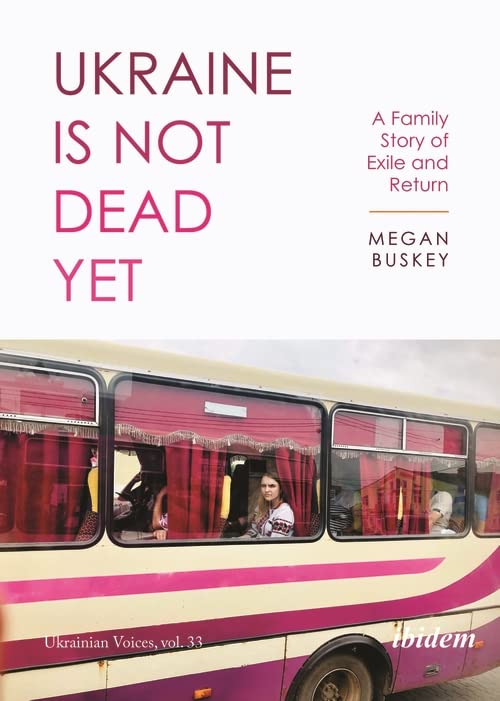

Born in 1982, Ms. Buskey now lives in New York, where she makes a living as a writer. “Ukraine Is Not Dead Yet,” her first book, is the story, foremost, of her grandmother Anna Mazur. The book’s title is derived from the first line of Ukraine’s national anthem. Although it resonates in the present day, with Ukraine fighting hard to get out from under Vladimir Putin’s jackboot, the title was chosen, Ms. Buskey tells us, well before the Russian invasion. More than just a commentary on the country’s condition, the fragment from the anthem reminds Ms. Buskey of how Ukraine “lived on” in her grandmother’s memory, “often as a site of trauma,” long after she came to the U.S.

It was through her grandmother, and her “foreignness,” that Ms. Buskey became conscious of Ukraine. She and her siblings, ensconced in their Cleveland life of almost embarrassing material excess, were particularly “flush with clothes.” Grandma Anna, who lived nearby, would box up the most neglected of these garments and mail them to family members back in Ukraine. In the months that followed the dispatch of the care packages, Ms. Buskey would find photos of relatives at Anna’s house and feel jolts of recognition: “That was my sweater with the rainbow stripes!”

Growing up, Ms. Buskey wasn’t overly enamored of Ukraine, the land that Grandma Anna and her two daughters (Olga and Nadia, Ms. Buskey’s mother) had left in 1966. Nadia was 12 at the time and integrated quickly into Midwestern America. The more tongue-shy grandmother, by contrast, avoided speaking English in public to her dying day. A resentful Ms. Buskey was made to attend Ukrainian school every Saturday morning and dragged to Ukrainian-language services at an onion-domed church just outside Cleveland’s western boundary.

Church was her grandma’s social highlight, a place where her “small, hobbling friends would flock to her like pigeons spying a bread crust.” It was not until Ms. Buskey went to the University of Chicago that she embraced her own Ukrainian identity with anything approaching enthusiasm. After she graduated, a Fulbright fellowship took her to Ukraine, where she immersed herself in her family’s story and in the history of that “beautiful, imperfect, singular country.”

It is a country we are all now coming to know, so that Ms. Buskey’s personal journey into historical comprehension has a rough parallel with our own fitful attempts to grasp the geopolitical conundrums that beset the Ukrainians. Part of such understanding is an awareness of Ukraine’s long and tangled history with the Russian Empire and, in the modern era, with the Soviet Union, from which Grandma Anna and her daughters had been able to emigrate—a near-impossible feat at the time—only because Anna’s father was an American citizen.

Link to the rest at The Wall Street Journal